via PRINT Mag:

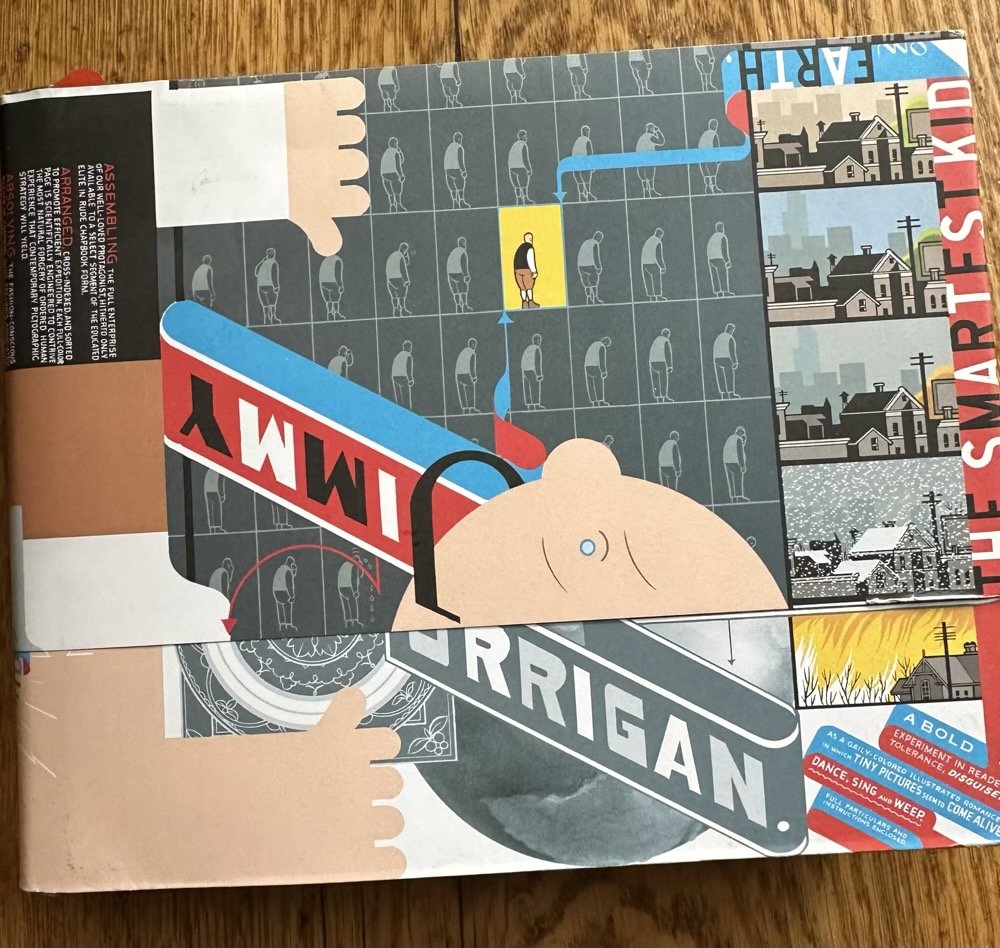

Comics drawing, aka cartooning, has more in common with typography than with traditional drawing: the drawings in comics are meant to be read, not just looked at...I tried to teach myself to handletter by looking at examples of 1920s original commercial art, specifically those done for the Valmor cosmetics company, original scraps of which were sold by the Chicago novelty store Uncle Fun and run by Ted Frankel, who had inherited the company's entire back catalog. I learned more from looking at those old inked and whited-out boards than I did from all of the old instruction books I tried to puzzle out, which always seemed reluctant to give up their secrets. These Valmor originals, many of which were by African American artist Charles Dawson, also affected the way I ended up drawing comics, which was to work more typographically than drawing-ly, for lack of a better word.